Writers have always held a special place in society. Be they the bard, whose words are said to channel the collective consciousness of their people. Or be they an individual stylist, the type of writer who delves into the murky depths of their psyche, and plucks fantasy from within. Then there are writers who blend both tendencies, weaving their understanding of a broader folkish sensibility with their own interpersonal experience, often using forms of auto-fiction to do so. One such master of this kind of synthesis was the 20th century figure Yukio Mishima, whose works function as a window into both his own troubled mind and the Japanese spirit. The themes of his novels are often heavy, with his debut ‘Confessions Of A Mask’, containing complicated psychosexual meanderings and aesthetic musings, wrapped up in a tale of adolescent ennui. Then on to one of his final works in ‘Runaway Horses’, we are told the story of a group of young men spurned by a form of romantic nationalism and a desire to reinstate the glory of the emperor. It culminates in a plot to assassinate state officials, and is representative of Mishima’s penchant for glorifying grand gestures involving death, destruction and rebirth.

What made Mishima truly extraordinary however, was his commitment to his own life as a work of art and as a lasting tribute to his philosophy of ‘Sun And Steel’. As illustrated in his transformation from an effete, sickly writer, and into a bodybuilding star of international renown, who would go on to cultivate his own private militia known as the ‘Tatenokai’. In November 1970, Mishima and the Tatenokai attempted to instigate a coup at a Tokyo army base, but it was an act that ended in failure. This set the stage for Mishima’s final, and perhaps most powerful statement: ritual suicide via seppuku.

Now, whether one looks at the life of Mishima as an extreme postmodern experiment in celebrity, or as a tribute to the cult of the samurai and a commitment to patriotic ideals, the fact remains that his visual legacy is a powerful one. Indeed, in many respects the photographs we have of Mishima summarise the man more succinctly than his novels ever could. Today his image finds favour in ‘vitalist’ circles online, and he has become a cult like figure for ‘sensitive young men’ and masculinity influencers alike. But whenever I have brought his name up to Japanese acquaintances in London, I am met with a sort of puzzlement, a confused laughter or even a slight disdain. It is clear that contemporary opinion of him in Japan is a mixed bag, and he remains somewhat of a mystery within even his own nation. None the less, the Mishima character continues to invite analysis and inquiry from across the spectrum. Today I wish to look at an element of his life that has not been focused on as much: his wardrobe.

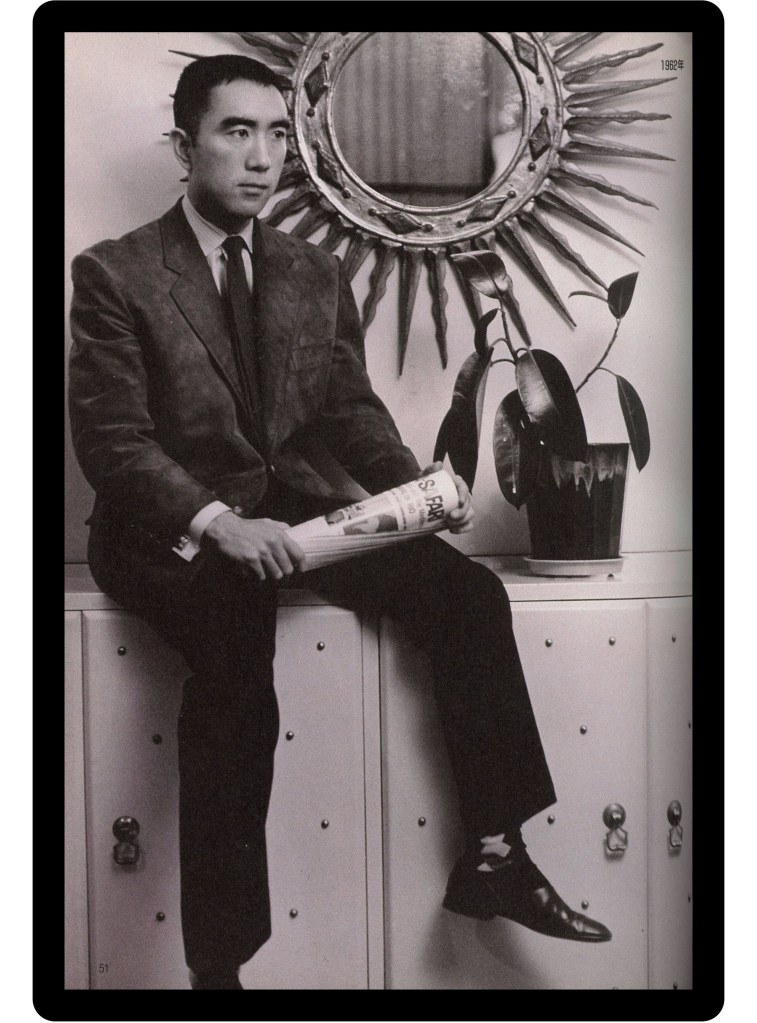

The sartorial choices of a writer can often tend toward the eccentric, due to the levels of individuality and idiosyncrasy such a profession can lend to a person. It was Oscar Wilde who provided a blueprint for the modern archetype of the ‘writer as dandy’, and was hugely influential for Mishima. But the influence of Wilde did not carry through to his fashion sense it seems, as upon reviewing two decades of photographs of him, one sees a rather restrained and refined personal style. A style that is of a clean and somewhat modernist variety, with some noticeable flourishes in garment choice that I will delve into here.

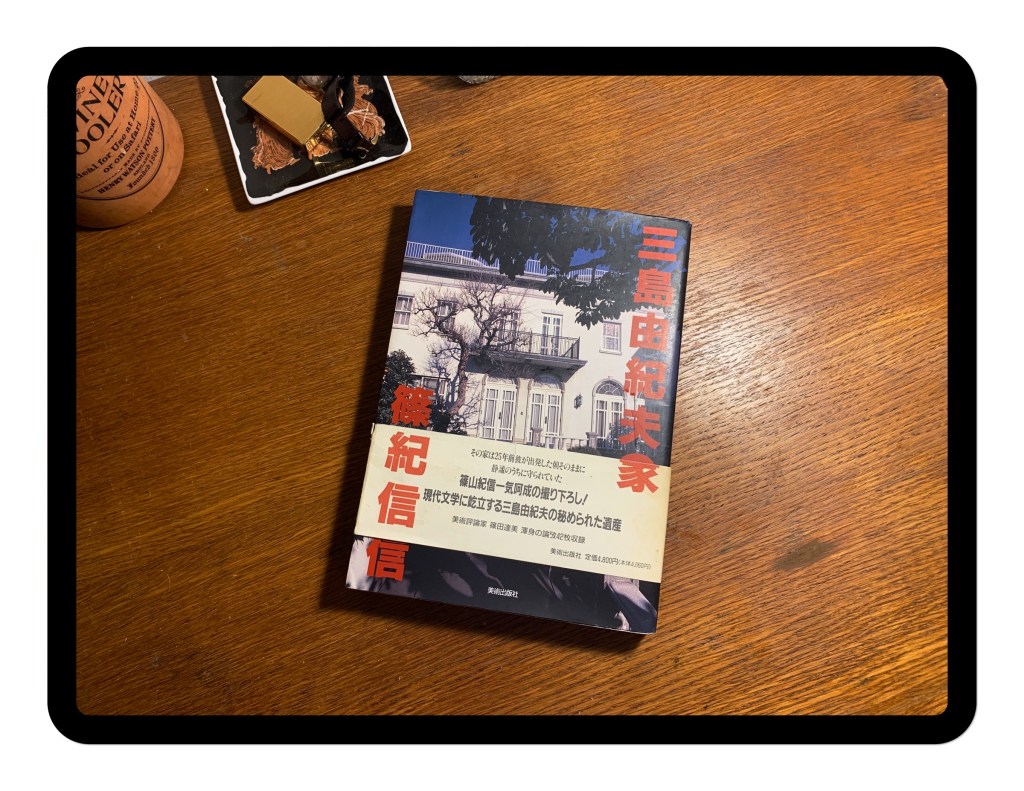

There are a good amount of photographs of Mishima online, but alot of them seem to centre around his more bombastic moments, either in his Tatenokai uniform or in some state of nudity, brandishing swords and such. In light of this I thought I would look for a more curated resource to glean a potential sartorial analysis. I arrived upon the book ‘The House Of Yukio Mishima’ which, as the title would suggest, is about the man’s house. It was made only for the Japanese market, but was well worth my importing it. With a series of gorgeous shots taken by the master of naturalism Kishin Shinoyama, we are provided with an intimate tour.

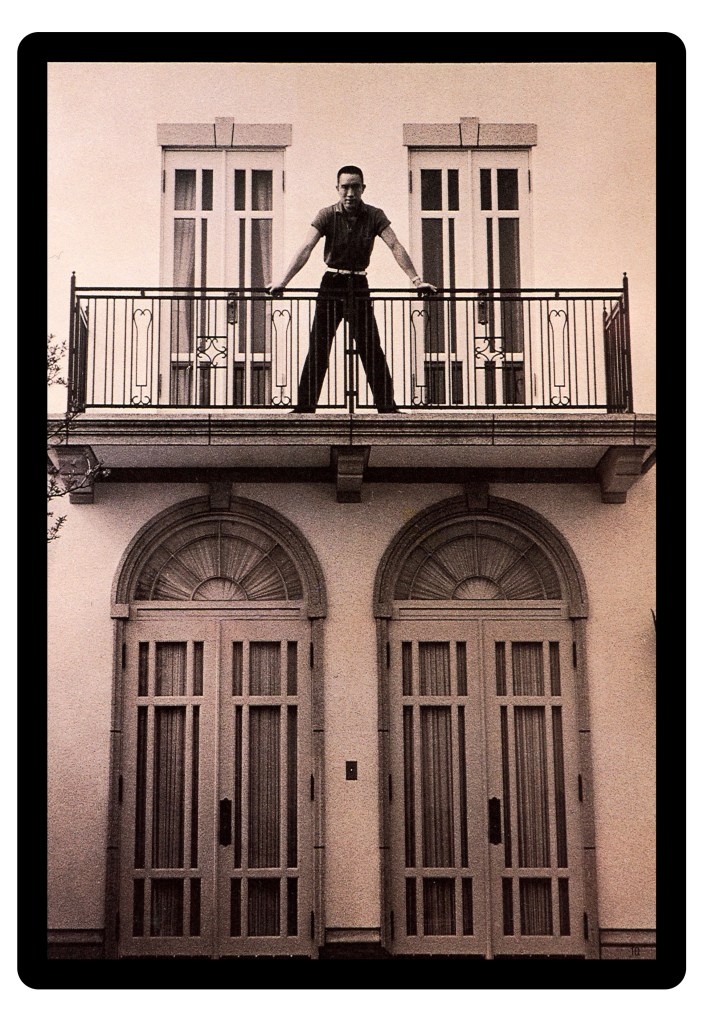

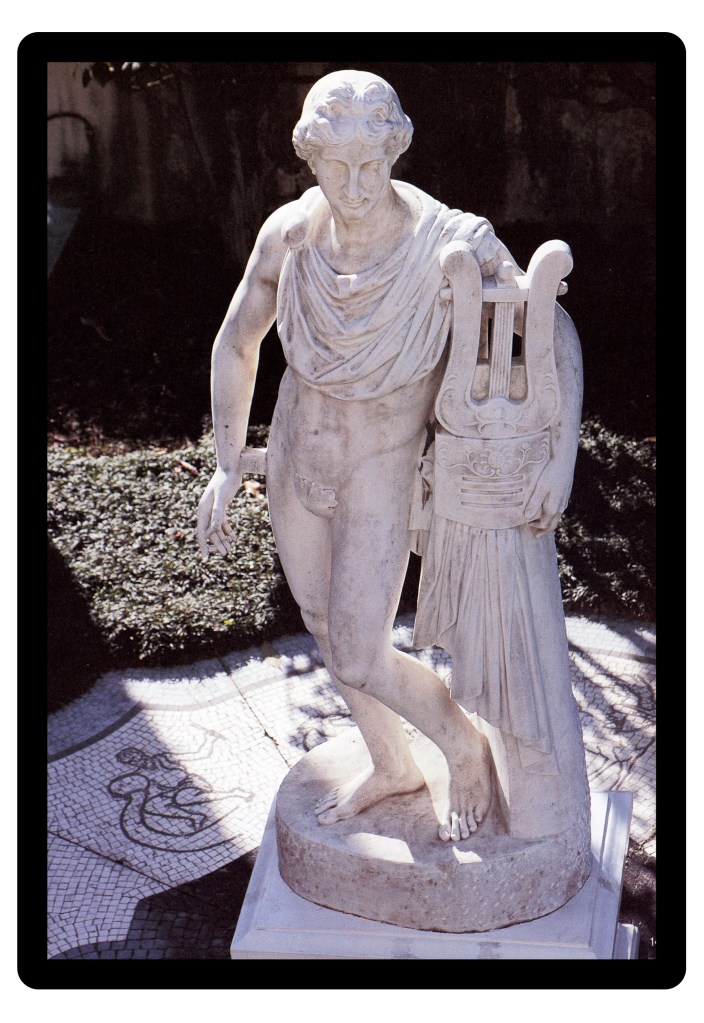

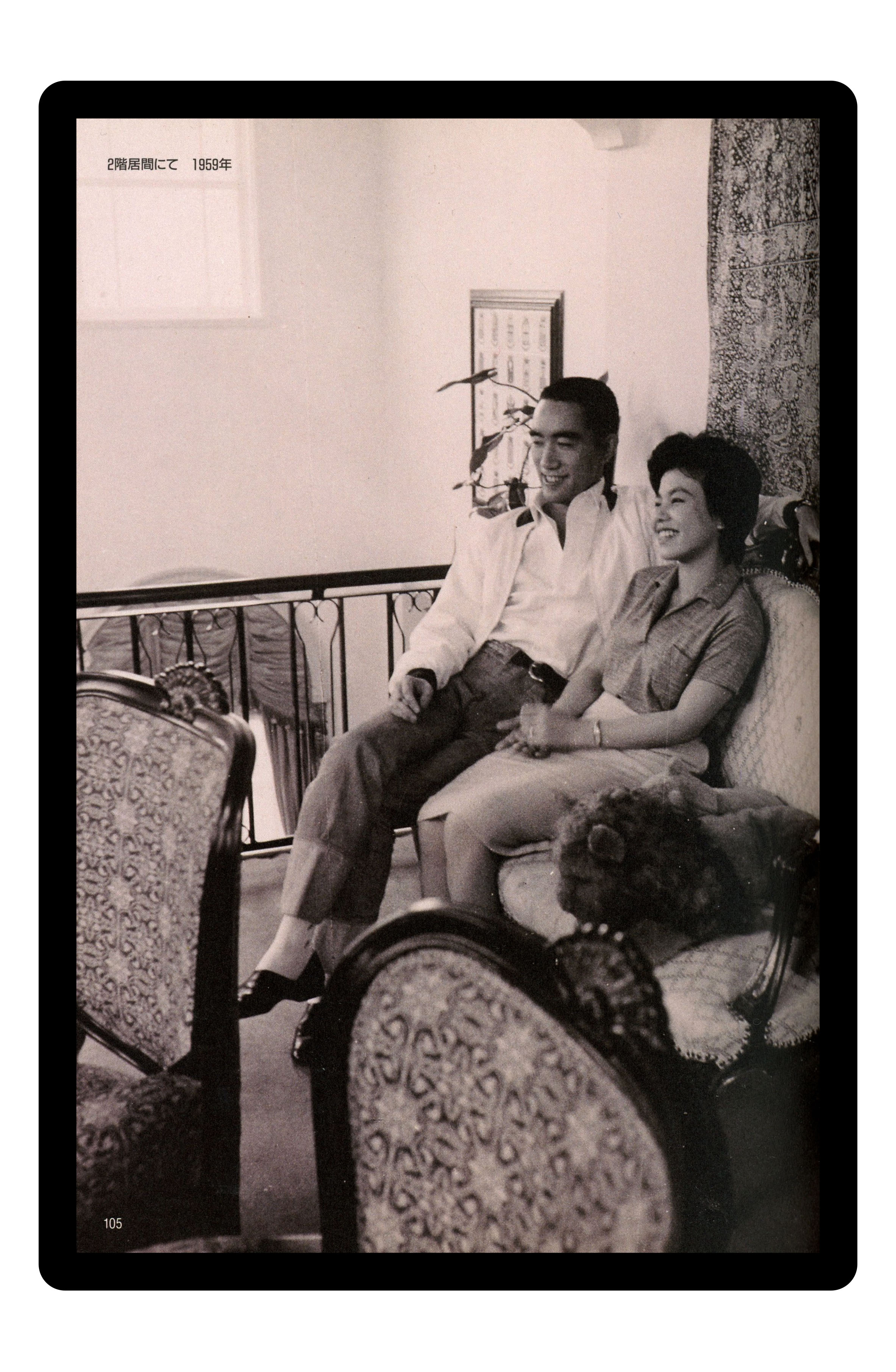

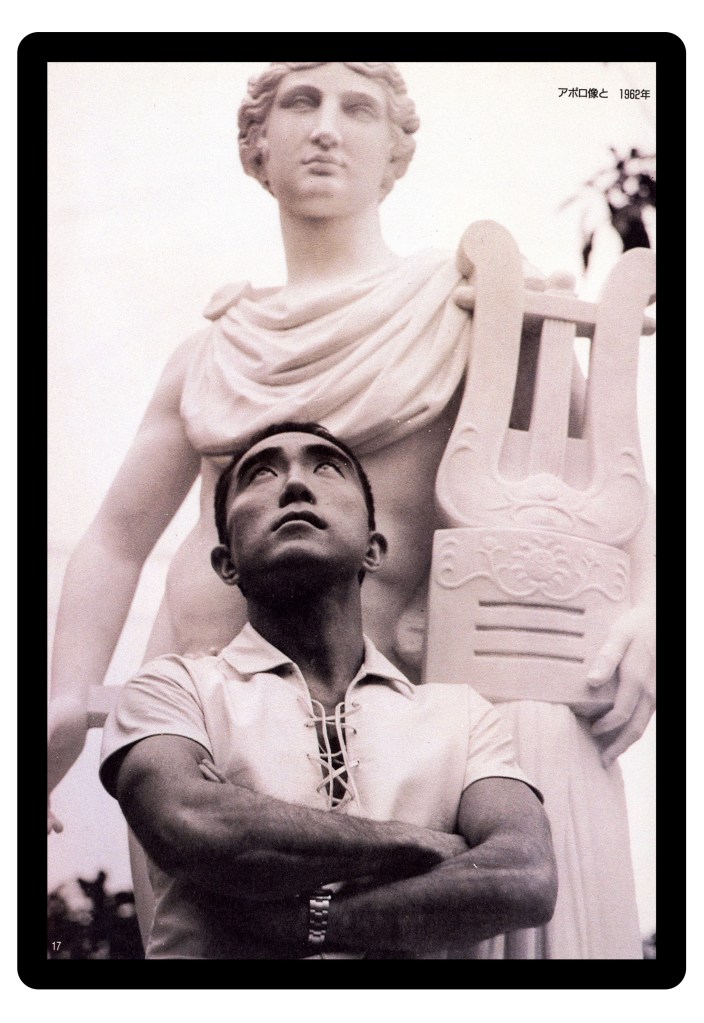

The house’s facade sets the tone for a classically inclined man, being made up in an architectural vernacular akin to a variety of French Neo-Classicism or perhaps a Regency Period townhouse. There is a small front garden, and in it stands a statue of the sun god Apollo, representative of Mishima’s solar world view. In keeping with the scale of building in Tokyo, the structure is rather compact, featuring humble living and dining areas decorated with pared back Baroque furnishings and immaculately curated antiques and ephemera, acquired on trips to Europe. There is a sizeable section of the book dedicated to Mishima’s study upstairs, and there are also some photos of an observatory style room with a uniquely designed rounded sofa.

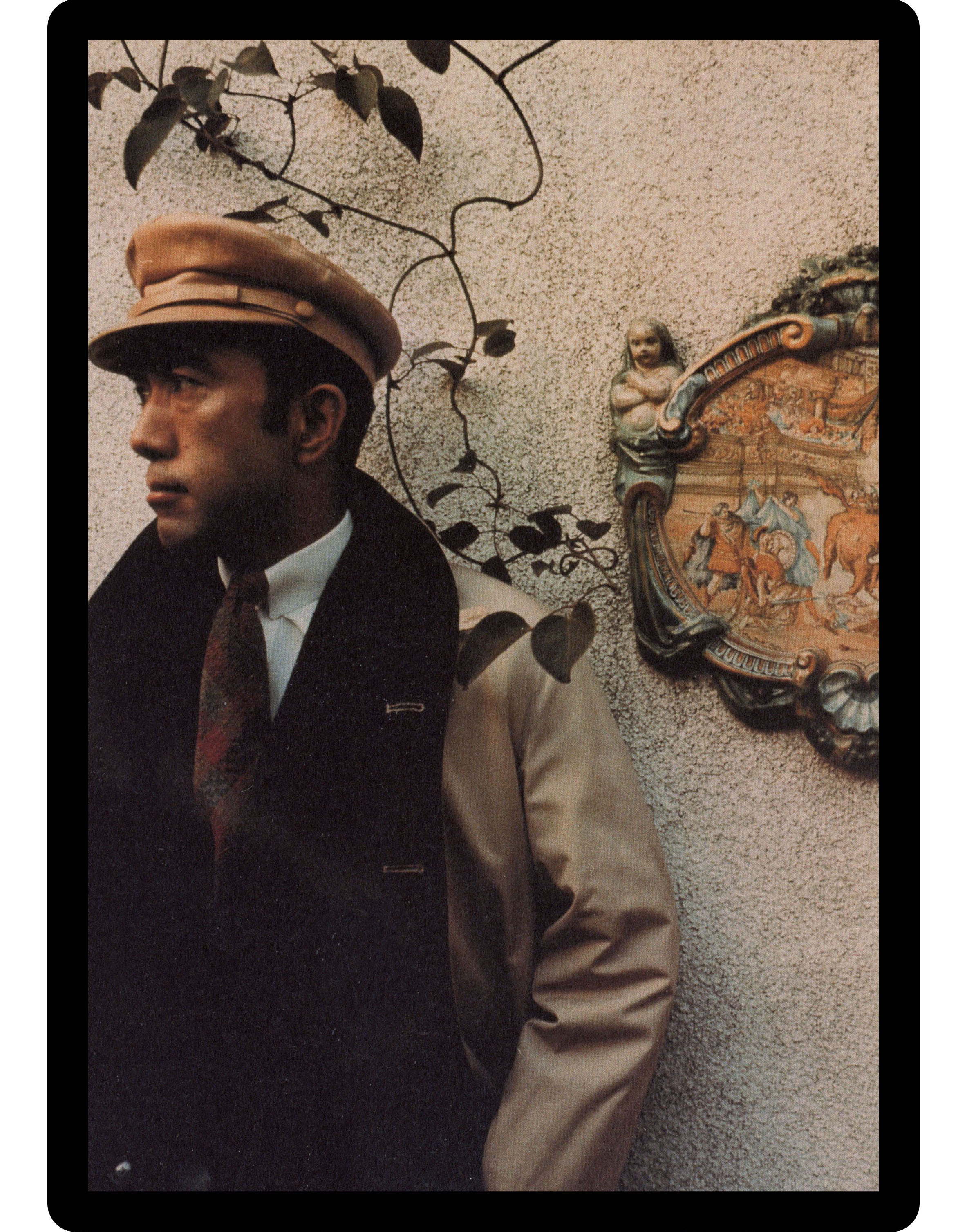

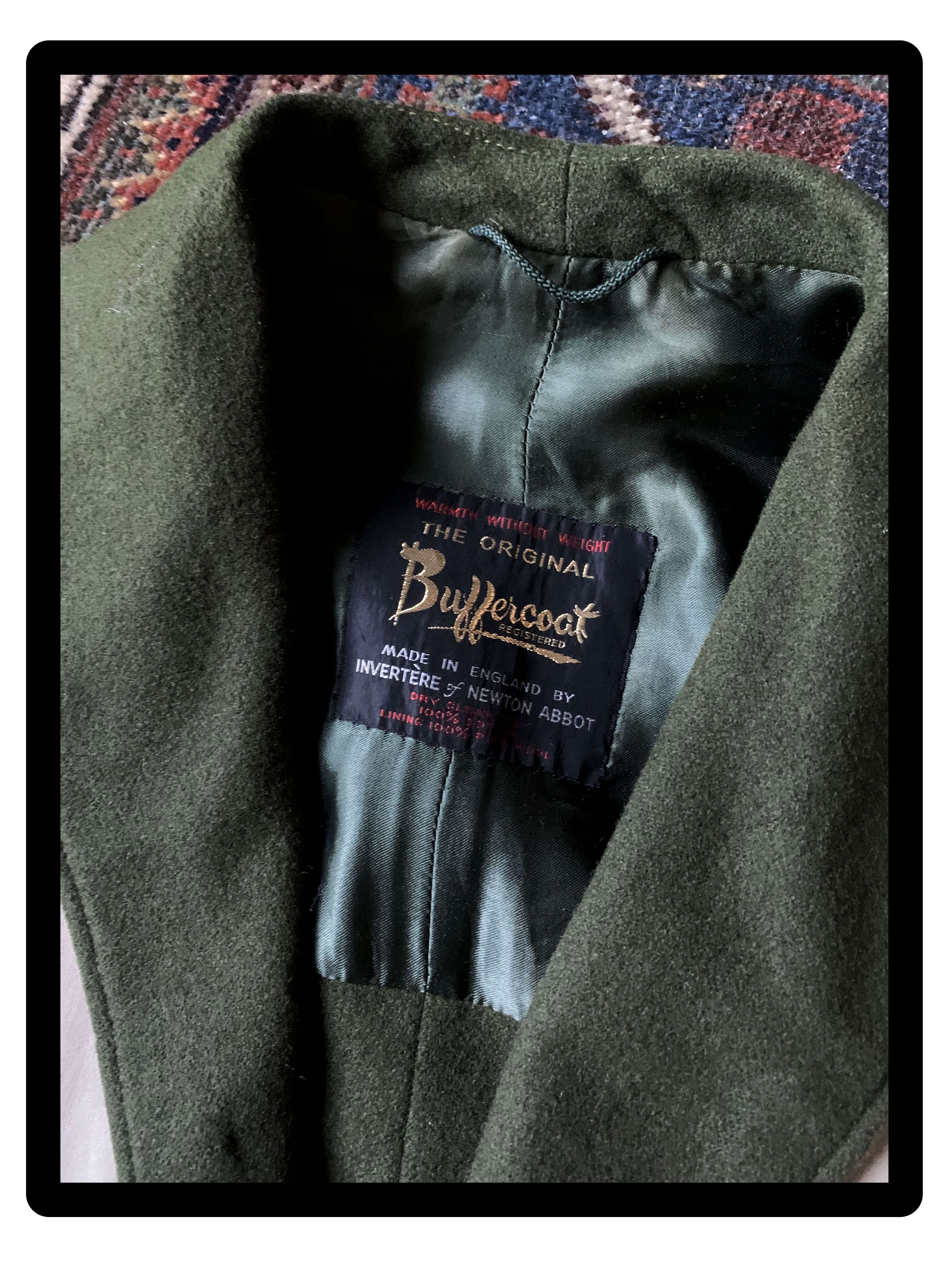

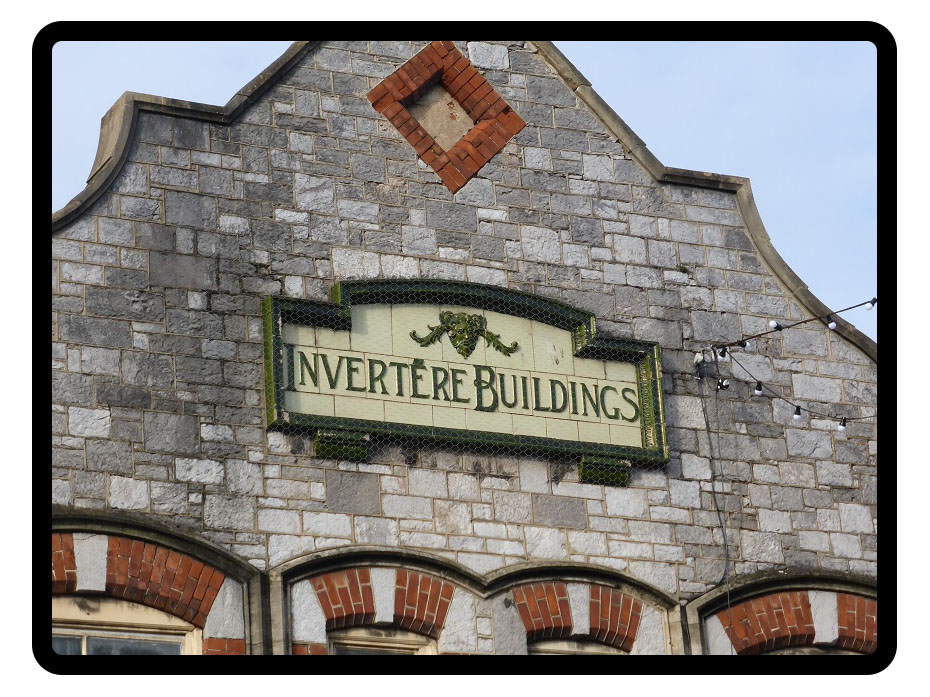

Interspersed between the liminal portraits of the rooms are some choice shots of Mishima that display his taste in dress. I was particularly pleased to see an image of him wearing a style of jacket known as a ‘Buffercoat’. A rather esoteric example of English country wear, the Buffercoat is marked by its distinct shawl collar which can be flipped up and fastened via a tab in order to provide a ‘buffer’ against the wind. It almost certainly would have been made by the famous ‘Invertere Of Newton Abbot’, who were a British coat manufacturer that produced under their own label, and also for Daks. Both brands were once owned by the department store Simpsons Of Piccadilly, so it is likely that Mishima would have picked up his one on a trip to London.

Another interesting choice is found in Mishima’s footwear selection. Specifically he appeared to enjoy a Grecian style leather slipper, and is shown wearing his pair with Argyle socks. This design of slipper is a great medium between the very casual backless ‘mule’ slipper and the more formal Prince Albert. Church’s have always supplied all three of these styles, and I am inclined to believe Mishima would have acquired his from them. I associate this slipper with the type of gent who likes to spend long days in his study, perhaps reading up on matters of antiquity. The Grecian then was a perfect fit for a man like Mishima, who would have wanted to maintain a certain elegance when brushing up on his knowledge of Ancient Greece and Rome.

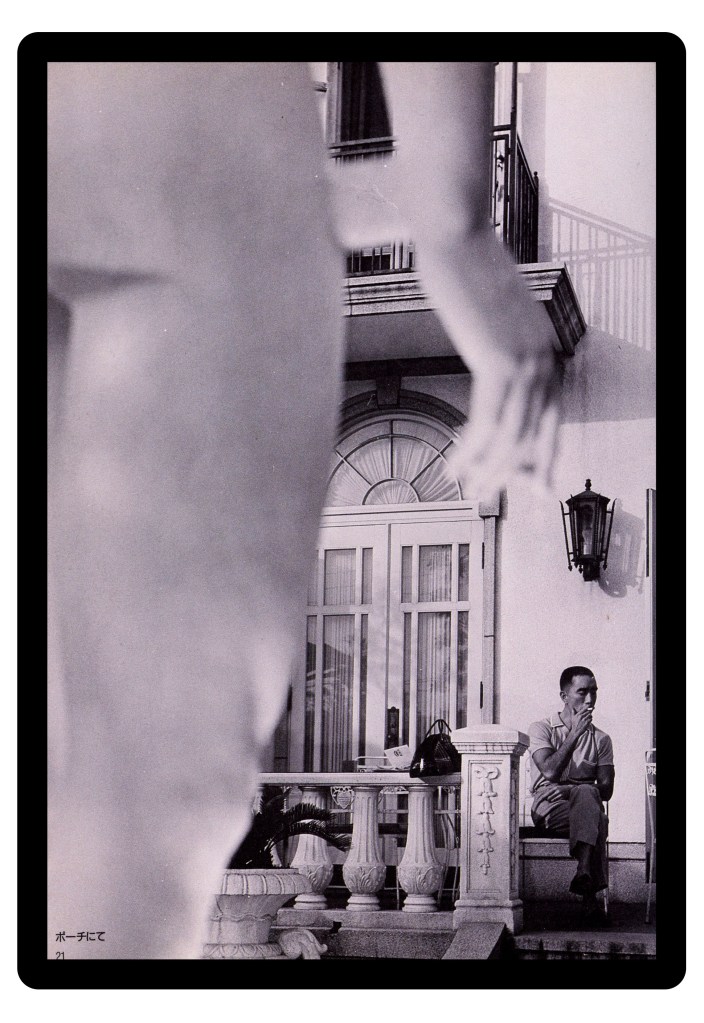

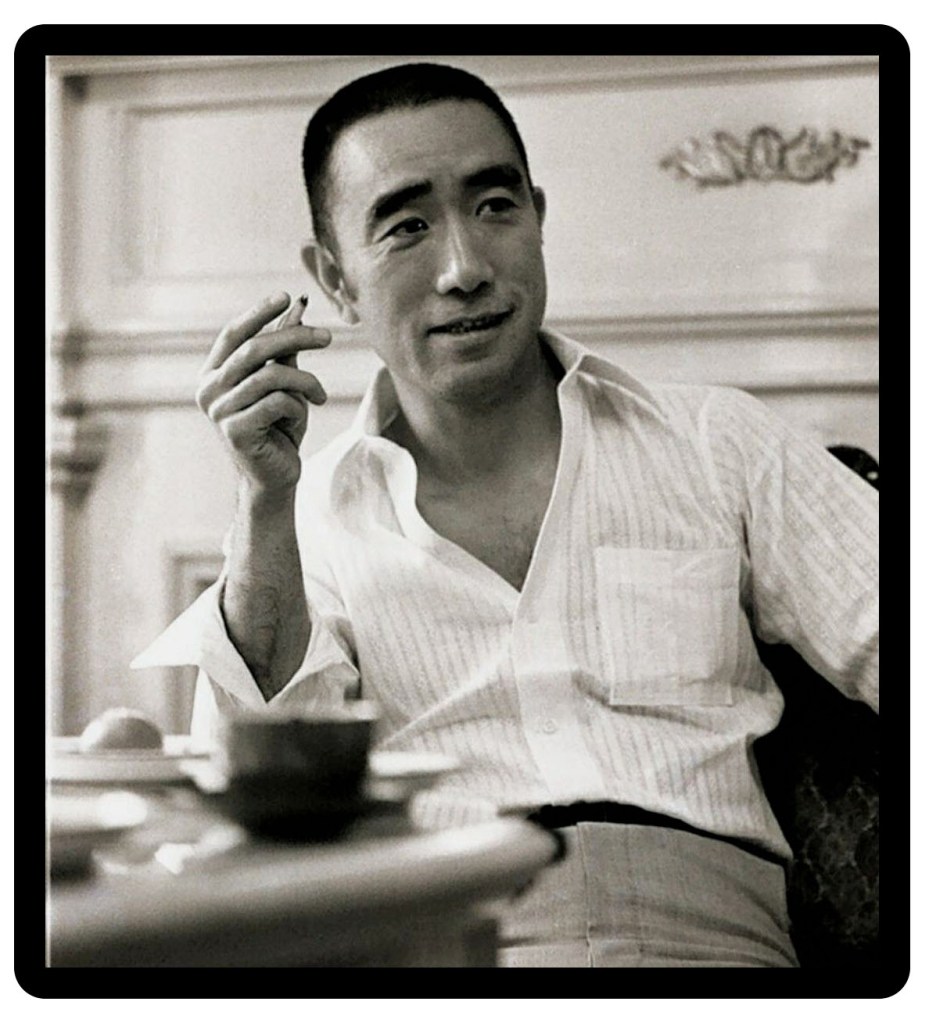

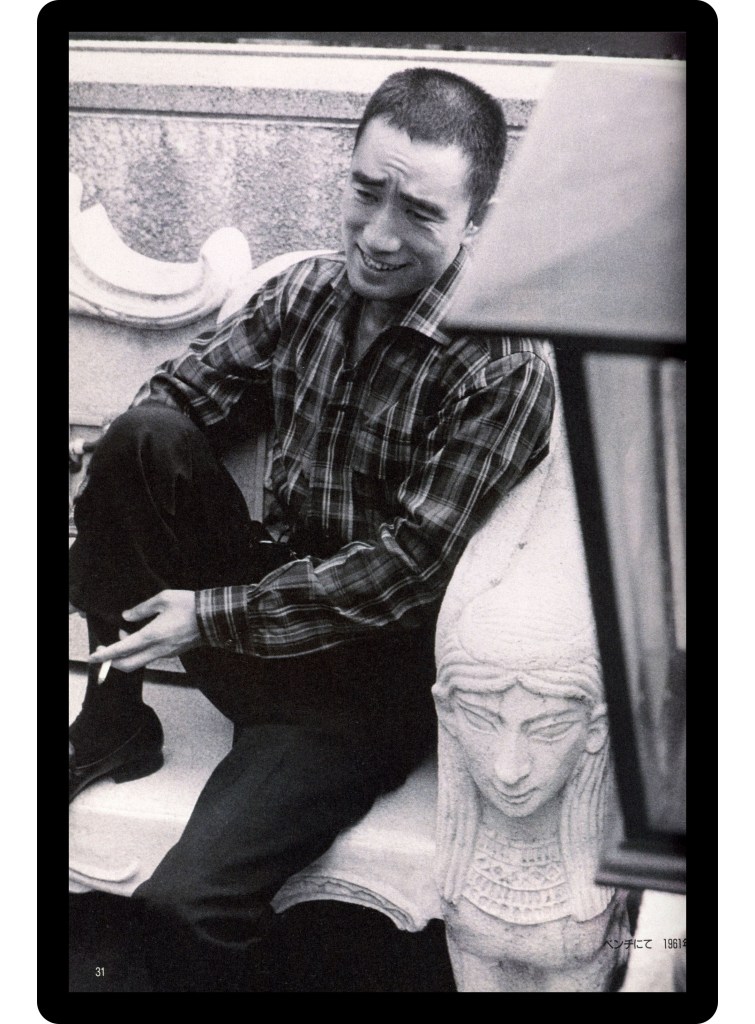

In another moment we see Mishima enjoying a cigarette in a casual outfit consisting of a Madras cloth shirt, slacks and penny loafers. He seemed to lean into these Ivy informed looks a fair amount, as there are lots of other photos I’ve seen of him in odd tweed jackets and club stripe ties. It is not surprising that such inflections would find their way to Mishima during this time. Teruyoshi Hayashida’s seminal ‘Take Ivy’ book released in 1965, and featured candid shots of well dressed students on the campuses of Yale and Harvard that would leave a lasting impression on male fashion in Japan. Ivy is the kind of style that is very much open to individual interpretation, and many get it wrong, but here I think Mishima gets it right.

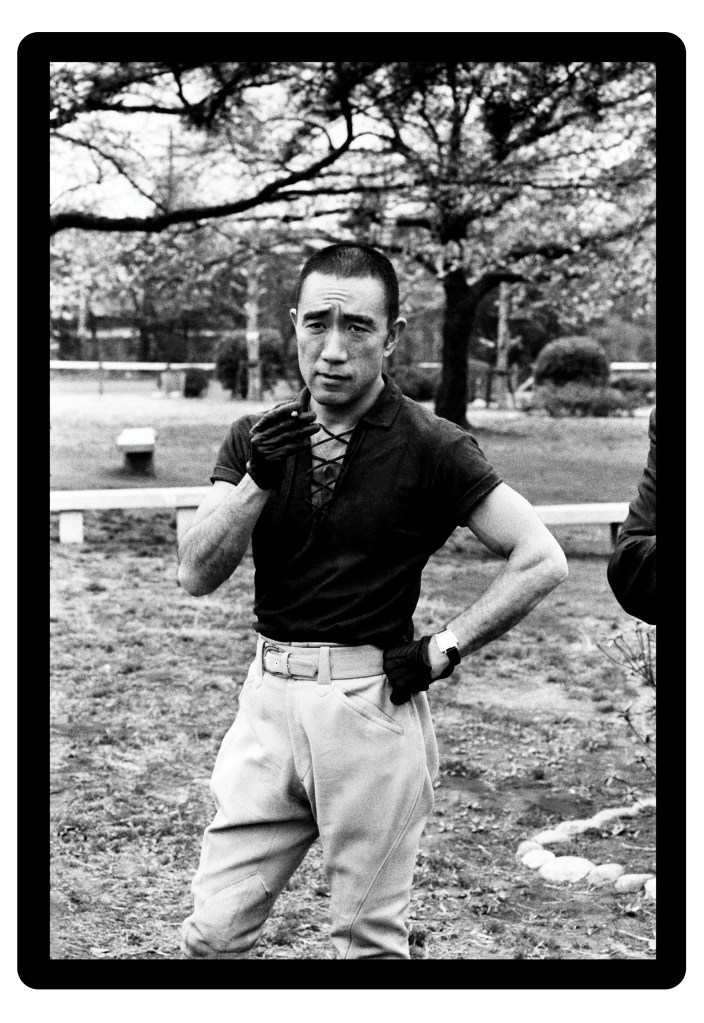

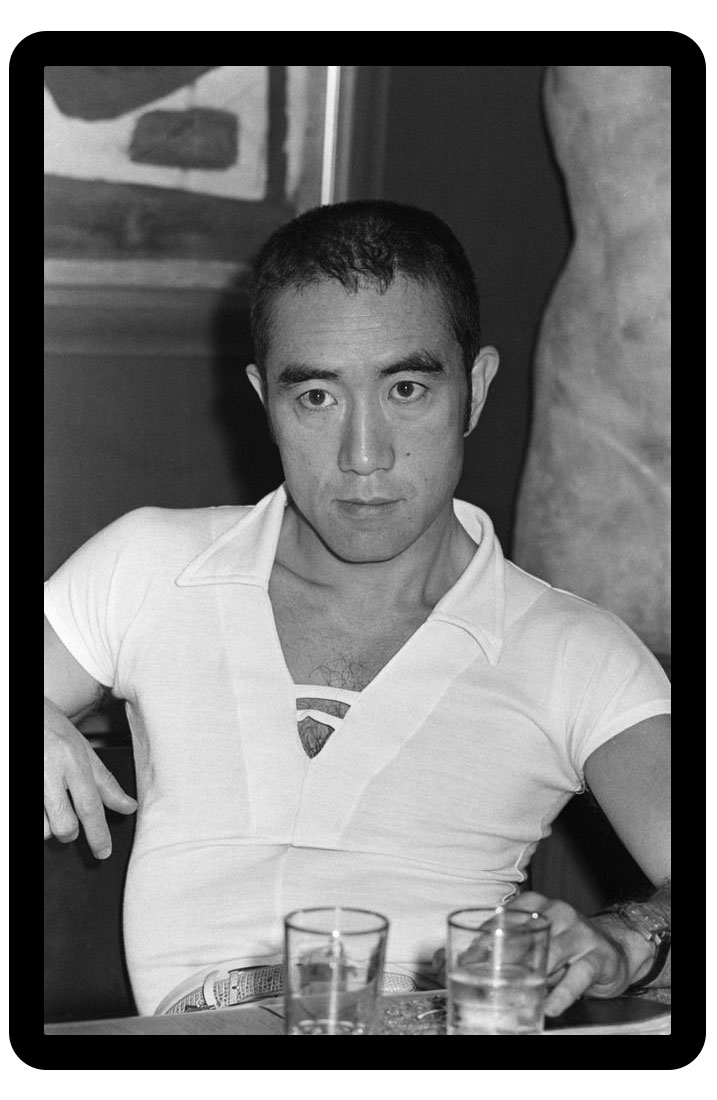

One recurring item you see Mishima wearing throughout the book and in photos elsewhere are polo shirts. His were quite eccentric by today’s standards, and were indicative of a more experimental period of mid-century design. This was a time when a polo may have been marketed as a ‘sport shirt’ or something along those lines. In the 1950’s through to the 1970’s, there was a lot of experimentation with certain details on these kinds of shirts, which you can see reflected in the styles worn by Mishima. In the book he is shown wearing one that has a very unique lace up collar. I suspect this was a detail appropriated from old Rugby shirts, so seeing it on a more ‘regular’ polo shirt with its finer cotton construction is quite unique (I have included another photo of him in a Black version that was found outside of the book).

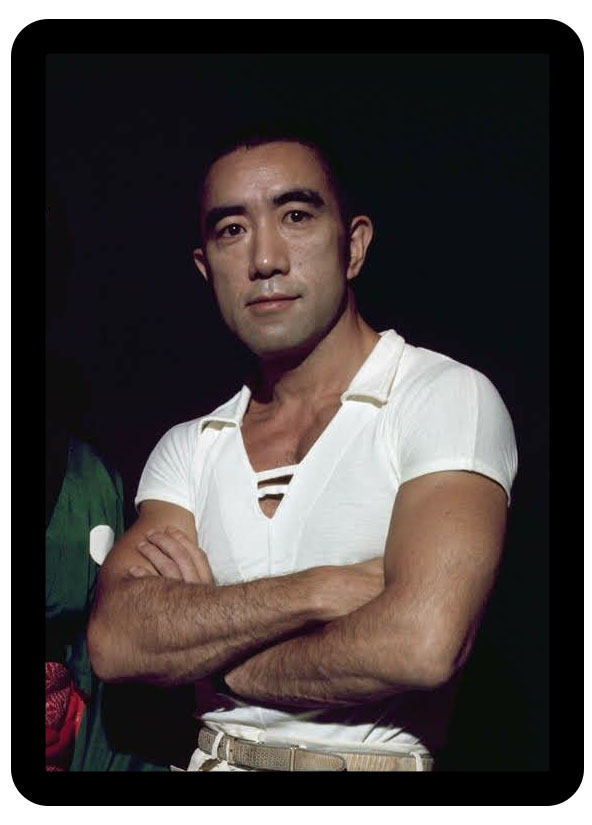

I have seen him in other interesting polos, including one he wore for a brief appearance in the surrealist gangster film ‘Black Lizard’. The polo is made from what looks like a kind of semi-sheer white cotton, and has a buttonless deep V Neck, with two bands across the bottom of the opening. It is unlike anything else I have seen. The angles and lines are reminiscent of an Art Deco sensibility, with clean shapes that cut just right. These types of ‘modern’ designs would fade out after Ralph Lauren’s preppy polos became hegemonic in the 1980s. But there has been a renewed interest in these older, more obscure styles, with brands like Brycelands and Scott Fraser Collection revisiting them. Perhaps Mishima’s polos could provide some new inspiration for the contemporary designer…

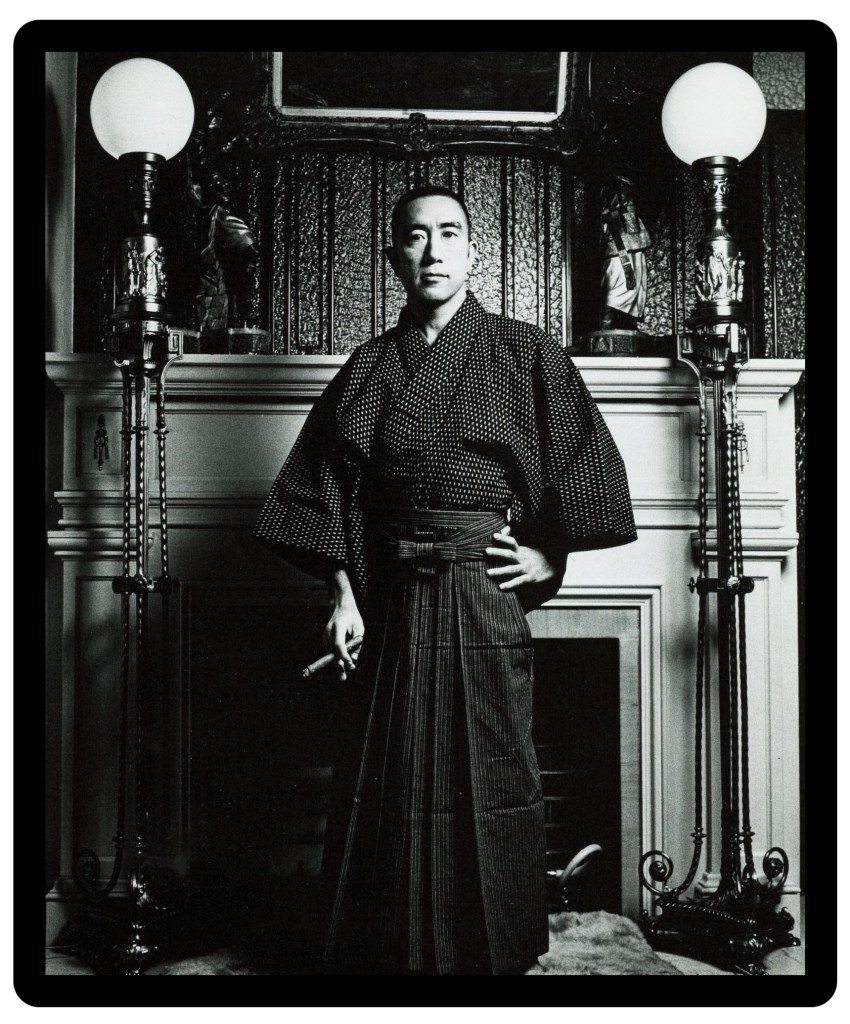

One of the few distinctly Japanese outfits Mishima wears in the book is this traditional ensemble featuring a Jacquard patterned Kimono and striped Hakama trousers. Standing next to his Art Deco lamps and with cigar in hand, he projects an image of a gentleman who is both rakish and refined. Worldly and outward looking, yet fiercely Japanese, with the credentials to back it up. One could potentially see Mishima’s home as a work of kitsch, a kind of attempt to recreate vague material notions of what it meant to be an ‘aristocrat’. But I think there was enough taste in his curation to show that really he was a man who desired to live anachronistically, both for reasons of personal enjoyment and as a rejection of the more vulgar aspects of modernity. As such his dress sense was a rather subtle affair that blended ‘trad’ elements with a handful of contemporary ones, forming a wardrobe that would not distract, but instead compliment Mishima’s journey toward his final destination: immortality via everlasting image. It appears he may well have achieved it…